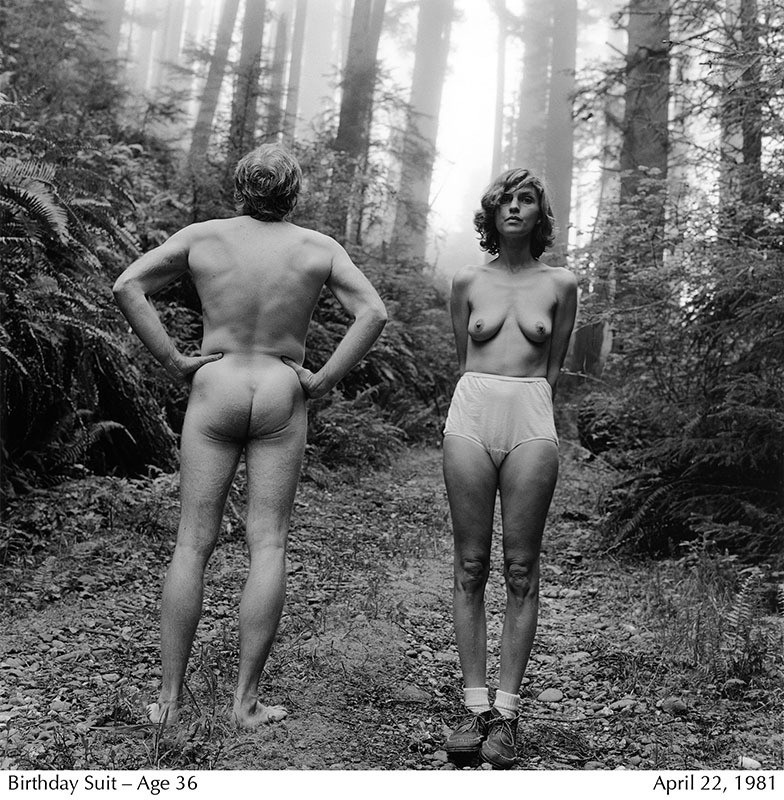

In child rearing, everything is upside down these days. People, parents, children are upside down. I show you the picture above because it’s where I grew up. Not to impress you with my personal provenance but to make a, to me, valuable point. This thing looks like a McMansion. Whoever has owned it since my parents did has destroyed it.

My dad bought it for about $2,500 in the late 1940s. It was a ruin, suffocated by ivy that was actively sucking the mortar from the bricks. The yard, all two and a half acres of a six acre plot surrounded by farmland, was a jungle. The previous owners had torn out supporting walls and annihilated the plumbing. The kitchen was a disaster, the second story leaked, and everyone on both sides of the family thought my parents were crazy for buying it.

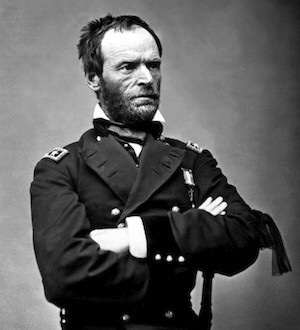

It did have a name. The Samuel Tyler House. The middle part that looks a smiling face was built in 1732. The larger wing to the left was added in 1815. A frame addition that has been replaced on the right was built during the Civil War. It was a rolling architectural history of America that my parents set about restoring.

When my sister and I came along we were loved but we were also labor. Scraping, painting, mowing, working. Vacations were not trips to Disneyland but projects. Heard the term house poor? That was us.

We had a pool in the shape of a fish. Left behind by the previous farm owners. No drain, no filters, but by God it was in-ground and we prepped it every year. The sewage pumpers came every spring to remove the muck of winter, and then we waded in to paint the interior and watched happily as the garden hose filled it was clear water. The tails of the fish had steps, so that’s how we learned to swim. Sit on the step, walk slowly into the deeper water, and daddy was always there to catch us.

As I got older, the lawn, the grounds, expanded. I mowed and mowed and dad kept increasing the size of the lawn. It was a dictum of his that weeds cut often enough would turn into grass. And at least, nicely mowed, they did look like grass.

As I’ve noted before, we also built a tennis court. Where I learned to play not well enough.

Throughout, the house and grounds kept getting better. The ivy was removed. The wings were united by white paint and period shutters my parents hunted at antique fairs or building demolitions.

The inside of the house was transformed. My dad turned an inside storeroom into a library he named the den, whose books I spent my childhood reading (and listening to all that Sinatra). The rotten floor of the 1732 portion of the house was replaced, for reasons of expense, with a concrete pour covered by thick carpet. But it worked anyway because there was an eight foot wide fireplace in which we had roaring fires, popped popcorn, and before which we played Anagrams and other games designed to make us smart. That room became our dining room. The place where I learned what utensils to use, how to use them, how to ask politely for someone to pass the bread, the butter, and the salt, and how to remember the state capitals when asked. But the utensils were sterling silver.

The house was, in spite of its provenance, never luxurious. Despite six fireplaces, the place never had any insulation, and we were cold all winter. There was one bathroom, not big, and a downstairs lavatory that was almost too small to use although the well water from there was always frigidly delicious.

If you go back to the picture, you can see a wing added on the left. My dad did that. (We all wire-brushed the ivy tendrils off the bricks of what was once an outside wall but now the centerpiece of a colonial kitchen.) It was time to get my mother a decent kitchen instead of the collapsing ruin of the Civil War frame mess, which got rehabbed into a study, a laundry, and a downstairs shower bathroom. We were living high by then.

You may have gotten the idea that my parents controlled my life utterly. But not as utterly as this:

A whopping 68 percent of Americans think there should be a law that prohibits kids 9 and under from playing at the park unsupervised, despite the fact that most of them no doubt grew up doing just that.

What’s more: 43 percent feel the same way about 12-year-olds. They would like to criminalize all pre-teenagers playing outside on their own (and, I guess, arrest their no-good parents).

Those are the results of a Reason/Rupe poll confirming that we have not only lost all confidence in our kids and our communities—we have lost all touch with reality.

“I doubt there has ever been a human culture, anywhere, anytime, that underestimates children’s abilities more than we North Americans do today,” says Boston College psychology professor emeritus Peter Gray, author of Free to Learn, a book that advocates for more unsupervised play, not less.

Truth is, I always had a kind of freedom few kids know these days. This patch of ground we called home was surrounded by farmland. I had hours every day in the summer when I could go back into the woods to a place called Little Egypt. It was my own private Middle Earth. There was a creek, a pond, trees to play Cowboys and Indians or Secret Agent in, and I did all that. First place I threw myself over my bike handlebars. With no one to tut tut. I could be there for hours and hours without any worry back home. Trees and vines and skunk cabbage and cap pistols and my dog, a German Shepherd named Mattie.

When I was fourteen I bought a truck to drive to Little Egypt. Bought it with $100 saved from mowing neighbor lawns. My dad initially resisted, thinking I’d been cheated, but he helped me paint it and turned me loose on the dirt farm roads. Mattie always rode with me. She died the first night I spent away in college.

You know, life is not supposed to be all fun, all penalty free. Even kids are responsible for what they do. But life should be some fun, as long as we can manage not to hurt ourselves too severely before we know what we’re doing. Risk is always part of the picture. My parents let me adventure in Little Egypt. Unsupervised. But they’d done their own homework. They knew that I knew what was right and what was wrong. And that’s why they trusted me to be entirely alone for four hours at a time.

The house in the picture. Don’t get it. I can hear the cell phones buzzing. Same address. Different place. God help them.

![Oh goody. I'm a conservative and I play nice. [Smile] [grrrr]](https://ip.rflaird.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/image9.jpg)

Recent Comments