Shuteye Town was always a book, unless it was your life.

I keep referring to a work called Shuteye Town 1999, which is presently available only in partial form here (Inspect the header). Thought I should explain its provenance at least. This comes from 2000 when it was released on CD/ROM.

Shuteye Town 1999

An Interview with R. F. Laird

Q: Your published works include an 800-page bible for baby boomers and a CD that presents itself as a video game. How do you get from bibles to video games?

A: The Boomer Bible was an attempt to write the scripture we have come to believe, which is different from the scripture we say we believe. It was satirical, of course, but it was also comprehensive, and it made some cultural predictions that came true so quickly they don’t even seem satirical anymore—less than ten years later. I felt that a follow-up was an appropriate project, aimed not so much at the parents as their X-generation kids. So I started to write a testament called The Zeezer Bible, which swiftly transformed itself into a kind of video game. I went with the flow, which is all you can do.

Q: You say it transformed itself? How do you start writing a book and wind up developing a video game? For the benefit of our audience I should explain that Shuteye Town 1999 is not a few text files with illustrations. It’s a 640 megabyte CD containing more than three thousand graphics files.

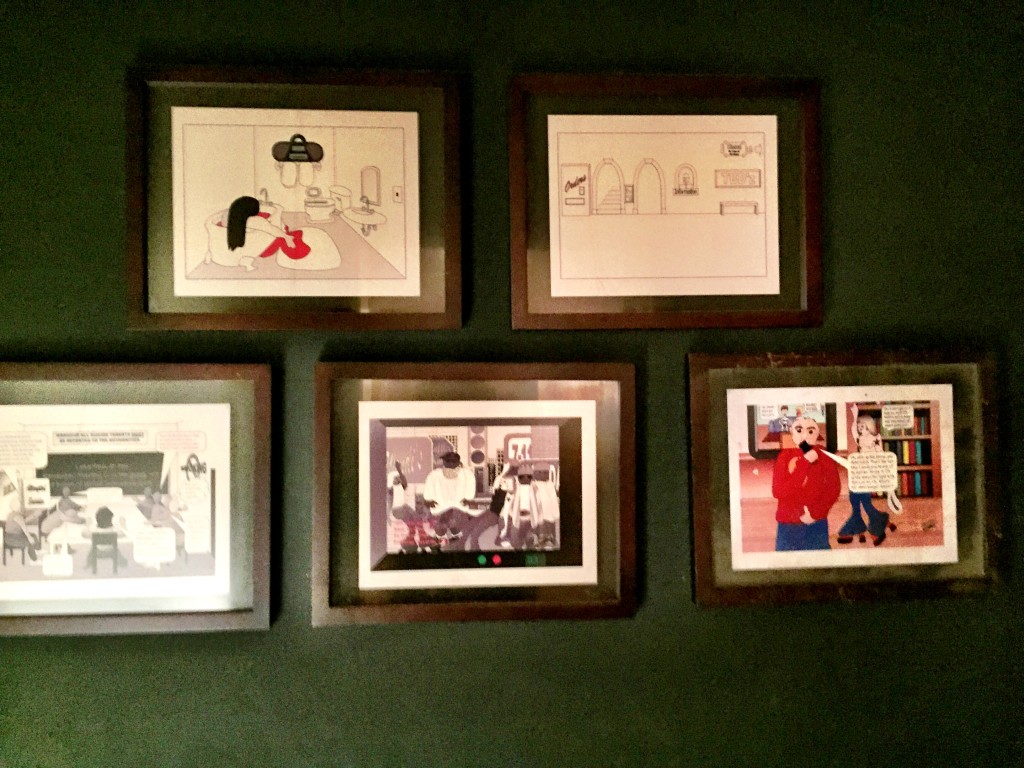

A: But it also contains almost 300,000 words of text. I started to write a book, but it quickly turned into a problem. Fortunately, the whole time I was working on it I had my fingers on the answer. The problem was that I was writing in an X-generation voice, or my version of an X-Gen voice, and the kids today know so little about anything that they can’t begin to convey a picture of the world they’re living in and what the absurdities of that world are. I was writing on a computer, in Microsoft Word, which has a built-in drawing package. So I started to draw a world around the text with the idea of showing in pictures and scenes what the words no longer could. It was the pictures that quickly filled in the outline of a place called Shuteye Town, where the reader could wander from place to place and occasionally bump into relevant text.

Q: What kind of a place is Shuteye Town?

A: It’s an underground city located in a nation called Ameria. It has a lot of things in common with the world we live in. It has a mall, ATMs, cell phones, four sports teams, a transit system with about 40 subway stations, a high school, a university, hospitals, hotels, a red-light district, two newspapers, ten channels of cable TV, a 10-screen movie theater, and its own version of the Internet, called the ‘UnderNet.’

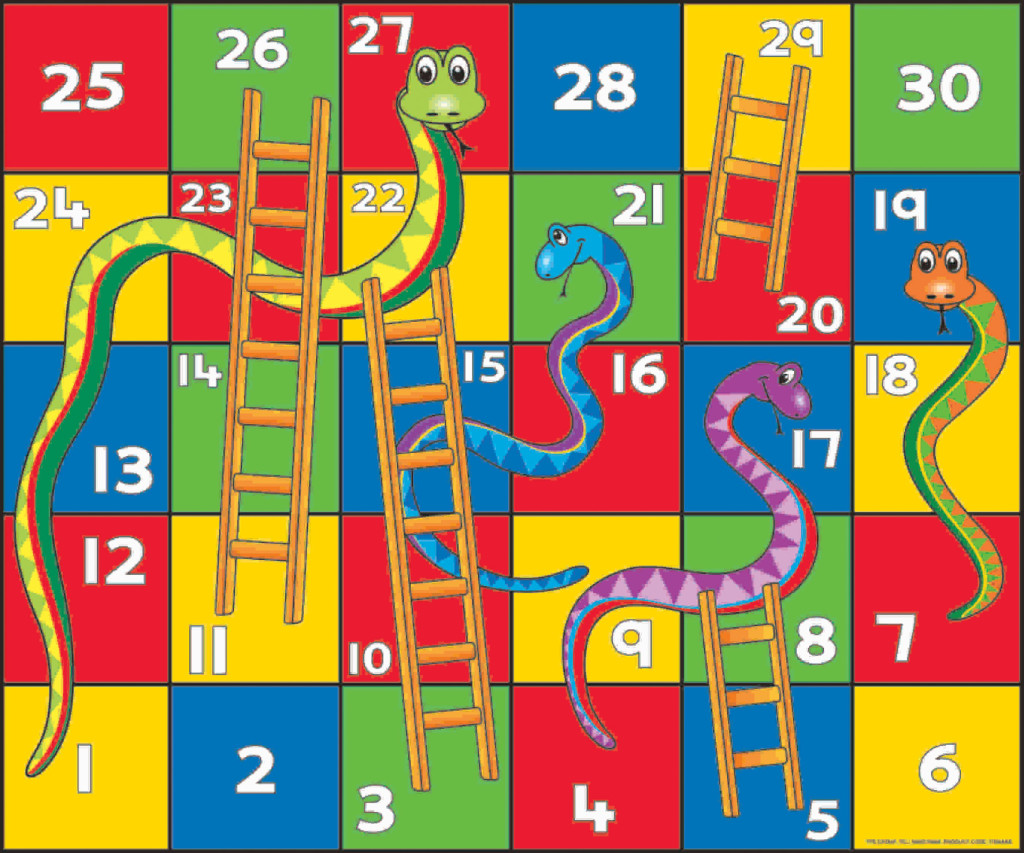

Q: If it’s a video game, what’s the object of the game?

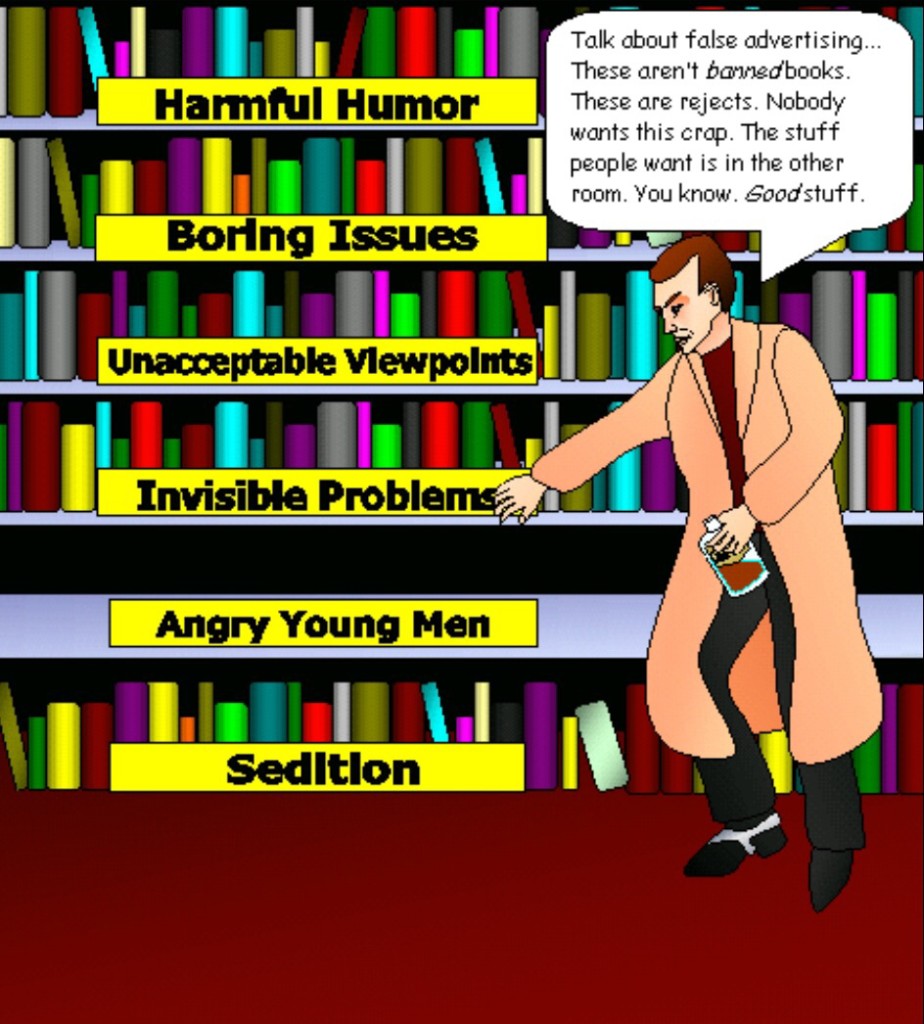

A: The reader, or player, has an identity in Shuteye Town. He or she is J. Doe, a faceless body of indeterminate sex who gets dumped into this world with nothing but a credit card that doesn’t always work. The object of the game is entirely up to J. Doe, whom I’ll call ‘he’ for the sake of convenience. At the beginning, he has to visit several stores at the mall to get clothes, so he won’t be arrested. After that he’s on his own. He can just wander around looking at things if he wants. He can browse at the bookstore, which has two hundred titles and numerous partial manuscripts, including several complete books. Or he can shop for a video to rent—he has about seventy to choose from. He can watch TV—about 30 shows worth. He can play video games. He can shop for a new face and even a new body if he wants. He can log on to the UnderNet and wander around in cyberspace. He can buy a newspaper, read the comics, and do crossword puzzles. But if he’s ambitious, he can go looking for all nineteen books of the Public Testament of The Zeezer Bible, which are not easy to find. For that he’ll need to figure out passwords, and he’ll also need to learn more about Shuteye Town. The prize is escape into another, quite different fictional world called Punk City, which also represents the only way out of Shuteye Town. I’ve been told that the objective of finding a way out of Shuteye Town can become quite an obsession.

Q: How do you think of it? As a book? Or as a game?

A: To me it’s a book. A new kind of book. The reader is the protagonist, and he gets to make up his own story. There’s a challenge for him to accept and maybe learn from if he chooses to, but he is free to decline that challenge or any part of it. He can read the writings I have made available, or he can ignore some or all of them and still have a unique experience. The point is, he is not my hostage. He doesn’t have to start at the first word of the first chapter and follow the single line that a printed book would draw for him. Instead he can pursue whatever intrigues his curiosity, if anything, and if that eventually attracts him to some or all of the writings, so much the better. It’s a nonlinear approach that also gives me more freedom as a writer. As far as I’m concerned, the old approaches don’t work any more. The world has changed, and most of the contemporary approaches to book writing trivialize both the writer and the subject matter to the point of insignificance. Unless new writing forms are developed to keep pace with the state of the culture, so-called serious literary writing—which is already irrelevant—will soon become as farcical as post-modern art.

Q: There are a couple of strong assertions in there. Let’s start with the first one. How do contemporary books trivialize the writer and the subject matter?

A: To explain that, let me point out a paradox. We keep hearing that the world is becoming a smaller place, that we are on the threshold of a global system in which no nation or community will be truly independent or apart from all the others. We are continually invited to think of the earth and its human cultures as a whole. But show me a writer whose theme and illuminations concern what we might call ‘the whole thing.’ Everything is addressed in slices, vertical or horizontal, and I am expressly including both fiction and nonfiction writers in this statement. Nonfiction writing is driven and deformed by a credentialing requirement that automatically conceals crippling biases which don’t have to be understood to be preemptively dismissed by the audience. For example, books about the law have to be written by lawyers, which is a lot like saying that books about tobacco have to be written by tobacco companies. I personally don’t think lawyers have the solutions to what’s wrong with the law, because they are part of the problem by virtue of the education that made them lawyers in the first place. The same principle applies to every other single subject in our culture. Politics. Gender. Race. Education. The mass media. Science. Healthcare. Crime. Economics. Religion. Child-rearing.

I’m not saying the so-called experts should be prevented from presenting their point of view. But I don’t think theirs is the only point of view, and I also don’t think I’m alone in believing that the experts are usually doomed to be wrong because of their very expertise. Each views the whole world through the lens of a specialized set of knowledge and experience that does not represent the whole and often distorts it. This has always been the case to some degree—more now than ever, I would argue—but historically, the role of fiction writers, including dramatists, satirists, humorists, and novelists, has been to describe the whole, that is, to present a unified context in which the absurdities and contradictions of ‘expert’ opinions are revealed. This no longer occurs. In this century, writers of all kinds of fiction have forgotten that their most important subject is life itself and what the individual experience of life may mean. They have chosen to become, like their nonfiction counterparts, narrowly specialized experts of one kind or another. Most are content to be expert journalists of the events of their own lives. Some are experts in one or more institutional arenas—politics, law, business. Some are experts in politically or culturally defined categories of experience—race, gender, sexual orientation.

Neither am I saying they can’t or shouldn’t make such choices. They are free to do it, and it is sometimes the case that a shaft of universal illumination beams from a very parochial lamp. However, we are sorely in need of voices that speak to the whole. Who is our contemporary Charles Dickens? Our George Orwell? Our Voltaire? Who is willing to shine a bright, unblinking light on the whole culture and look for the relationships between our manifold hypocrisies and our manifold failures, political correctness be damned? No one, it appears. Some pretend to this role, of course, but none whose most far-flung insights couldn’t ultimately be boiled down to a definite preference for one of our two bankrupt political parties. The inevitable symptom of overspecialization is the disappearance of new ideas. And any cultural form devoid of ideas becomes trivial.

Q: Are you suggesting that your own Shuteye Town is the Bleak House or Candide of the 1990s?

A: No. I’m saying that I’m a writer who is interested in the whole. And that in my work I’m trying to solve writing problems that don’t become evident unless and until you are interested in the whole. Shuteye Town is an attempt to solve some of those problems. Whether I have succeeded or failed in the attempt is not my judgment to make.

Q: What problems?

A: We live in the most complicated time in human history. We are supposedly—and quite loudly, I might add—devoted to raising a generation which can pace America to a second century of world leadership. And yet all the evidence indicates that this is a generation of youngsters who do not read—not literature, not magazines, not newspapers. Worse, they do not speak. Even network anchormen struggle visibly to extort a handful of understandable phrases from them when they are interviewed on camera. How is this not a catastrophe? And yet we all pretend there is nothing seriously wrong with them.

And if one is interested in this world-shaking circumstance as a writer, how might one go about discussing it with both the youngsters and their parents? If I craft a prettily written novel about the problem, who is going to read it? Some avid reader who will mutter ‘interesting’ or even ‘how true’ to himself? Do I render the inarticulate ignorance in all its ugly emptiness and puff two pages of interior monologue up to three hundred with writers’ tricks? Still, who will read it and to what effect? Or do I venture into a new realm where some other kind of communication bridges the gap left by words that are no longer there? That’s what I’m trying with Shuteye Town. Another problem. Political correctness has made it impossible for white males to speak honestly about two issues which are central to the health of society as a whole—the implications of feminism and the corruption of the civil rights movement. Yet if we do not apply serious and critical thought to these subjects, they have the power, singly or in combination, to destroy the very foundations of our culture. There is only one way to build enough room in a piece of writing for frank commentary on these two subjects—by establishing a context so all-encompassing and harsh that these subjects would be made even more visible by their absence or by kid-glove treatment of them. Shuteye Town has exactly that kind of context.

Q: All this sounds very serious and even angry. How does this square with the stated intention that Shuteye Town is a satire, that it’s funny?

A: It’s always a dangerous gambit to explain the mechanics of humor, but at the risk of shooting myself in the foot, I’ll try. Humor arises from unexpected juxtapositions that nevertheless cause some kind of recognition in the audience. Laughter is a completing of the circuit—it represents the instant at which some heretofore invisible contradiction, absurdity, similarity, or universality is recognized. The dignified dowager slips on the banana peel, and we laugh at the sudden recognition that she looks just as much of a fool when she falls on her ass as anyone else. The key phrase in this definition, though, is ‘humor arises.’ It’s hard, if not impossible, to engineer humor by analytical means. But when you start compressing the real world into a smaller space so that circumstances and notions which normally exist in different domains are pushed together, humor is frequently a spontaneous by-product of the process.

So what’s really required as a starting point is the realization that absurdities and contradictions do exist in our culture on a very grand scale. Then, when you start playing with subjects that people are inclined to take oh-so-seriously, funny stuff just pops out into the open. Now I must point out that satire and humor are not synonyms, and they are not even varieties of the same basic mechanism. Satire seeks to identify contradictions and absurdities for the purpose of provoking thought. To do this, it may employ humor as a device: the laughter of recognition signals the need for a thought process to begin. But satire can also achieve its ends by pushing its juxtapositions past the point of humor into the realm of fear and horror. The greatest satire of our century, in my opinion, is 1984. But is 1984 really funny? I don’t think there are too many Hollywood directors who would cast Jim Carrey as Winston Smith. What I will claim for Shuteye Town is that it is a satire, and satire is historically an angry form. If I have done my job right, Shuteye Town will also strike many people as funny. I would like that, even though I am angry about many of the subjects it touches on, because there are plenty of times when a joke is just a joke.

Q: But isn’t anger a red flag to a lot of people? Isn’t it basically a negative emotion, one which causes hurt and a reciprocal anger rather than the thought process you say you want?

A: It’s become very popular in America to wag our finger at anger and issue a stern ‘tut tut’ to anyone who raises his voice about something. This is one of the silliest by-products of the false assumption that the inevitable eventual outlet for anger is violence. That’s why we’re so much more censorious these days of male anger than female anger. We’ve been led to believe that when a man gets angry, he starts shopping for an automatic weapon. In a sense this is becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy, as we push people, particularly men, into the belief that expressing our emotions is more important than trying to think things through inside our heads.

Somehow it has become acceptable to criticize men for thinking too much and talking too little, while it has ceased to occur to anyone to criticize women for talking too much and thinking too little. In my opinion, it would behoove us all to think a great deal more and to allow ourselves to become passionate about what we think. In the realm of the intellect, anger can be a powerfully positive force. It energizes the mind to break through the barriers of convention and tradition for the purpose of finding helpful new ideas.

I suspect that it is precisely this property which underlies the current hostility to anger as an emotion. The emperor is now so stark naked that we have all come to share the same deep subconscious fear that someone may dare to speak of it out loud and laugh. And most of us are as naked as the emperor. We don’t know why we’re leading the lives we are. We don’t know what we have in mind, if anything. We don’t know what it’s all about, if anything.

And we don’t know if we even want the question asked. But in my anger, I insist on asking the question. My daring to ask may indeed anger some people. I’m convinced, though, that those who are capable of thinking will react to their own anger by thinking anew about the beliefs which have been outraged by my perspective. And those who are not capable of thinking cannot be reached by any approach other than total agreement with their existing biases and notions. I have no interest in reaching people like that. They are already mortally wounded. All they could ever want from writing is comfort, and they can get that from plenty of sources.

Q: You make writing sound like a kind of warfare.

A: It is. It is the responsibility of a certain percentage of people in any culture to think and to keep thinking about the big subjects—where we’re headed, why, whether we should change direction, and if so, how. It is the responsibility of a certain percentage of writers to be a pain in the ass to those people—to make them think harder if they’re already thinking, and to make them start thinking if they’ve stopped for any reason. And when the culture as a whole tips into a precipitate state of decline, as ours has, then the urgency of that responsibility is indeed akin to a state of war: the stakes are life-and-death, the consequences of inaction are catastrophic, and all will be affected by the outcome.

Q: Why do you say our culture is in a state of precipitate decline? What’s your evidence? Can you explain why you’re so alarmed in terms that people can understand?

A: I’ve already taken my best shot at that. It’s called Shuteye Town 1999. If you have a Windows PC, you can find out for yourself what I’m upset about. If you don’t have a computer, you can get started with The Boomer Bible and visit Shuteye Town later on.

Q: Since you’ve taken the opportunity to plug your book, let me ask you a tough but pertinent question. If you’re intent on reaching youngsters as well as their parents, why does Shuteye Town carry a Parental Advisory sticker warning of Explicit Content. Isn’t that hypocritical, or at least counterproductive?

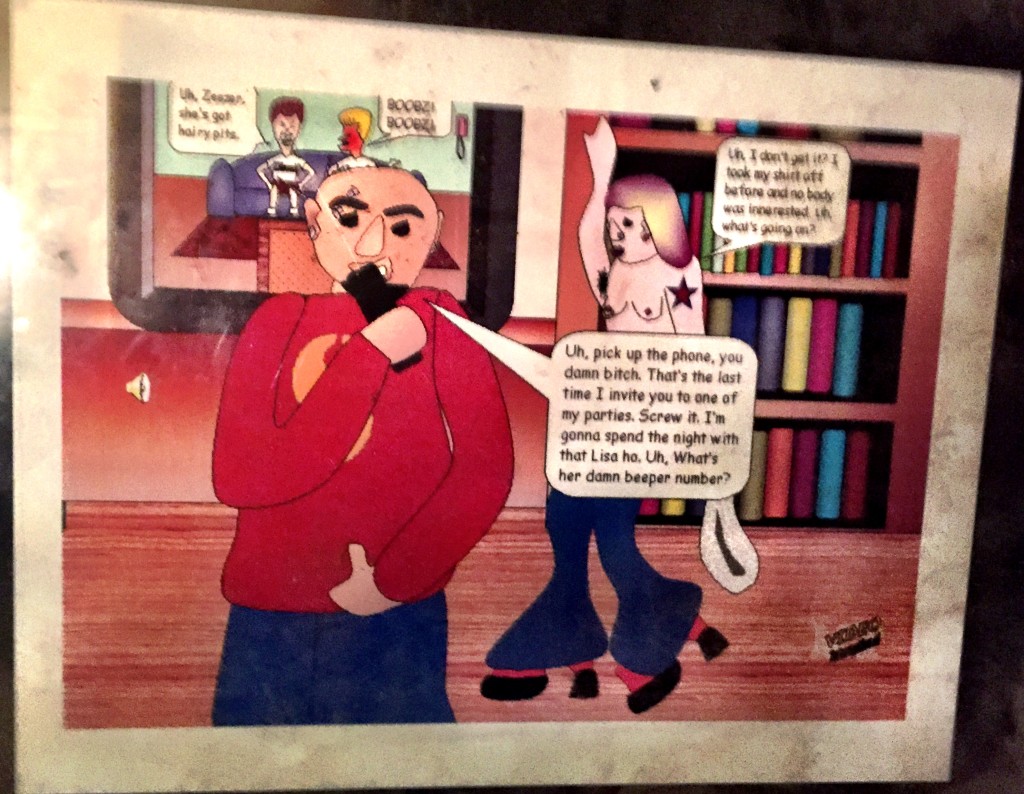

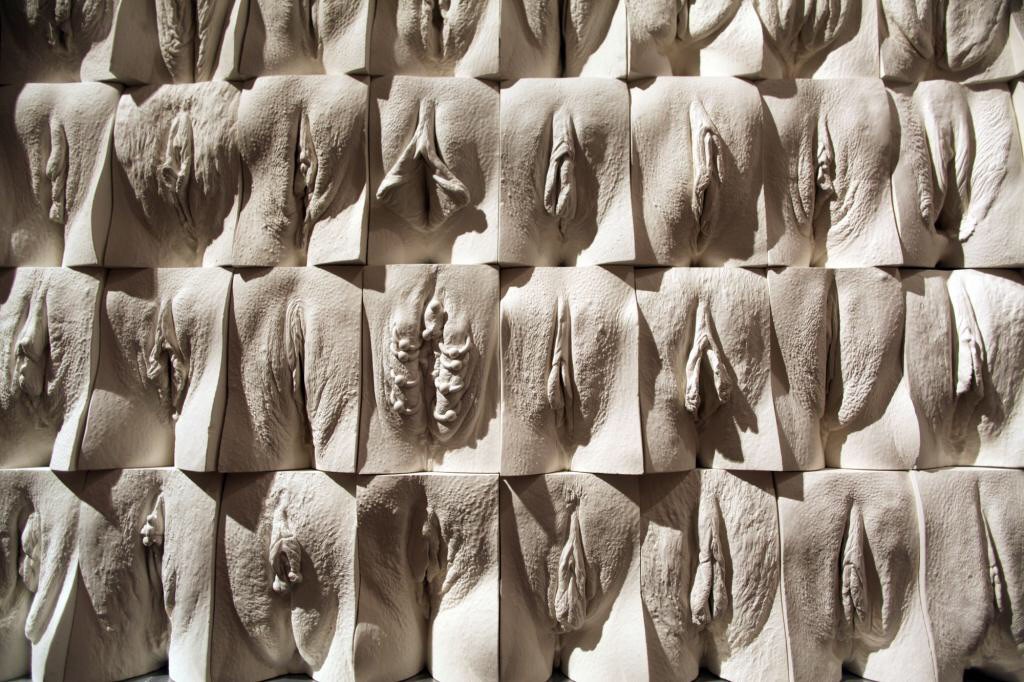

A: It’s a necessary compromise. How does one go about rendering a culture like ours? One of its most startlingly visible features is its vulgarity. Our language is foul, our entertainments—public and private—are filled with leering sexual images and pursuits, and all the media are saturated with images of violence, crime, and sexual deviancy. To omit these aspects of American life in a work that seeks to comment on the health of the society as a whole might constitute a virtuous sacrifice, but it would also constitute an act of concealment. If my only purpose were laughter, then it might be acceptable to allude to our pervasive vulgarity without showing it. But my purpose goes beyond laughter—how, for example, can I demonstrate that technology has made voyeurs of us all, even the most self-professedly moral among us, without awakening the voyeur in the reader? And so I have opted for a species of imagery and language in Shuteye Town which is, in some respects, as vulgar as the culture it depicts. I accept that this costs me the right to solicit an audience under the age of seventeen; however, I am not so naive as to think there is any content in Shuteye Town that exceeds the explicitness of what the average thirteen year-old American child has already been exposed to. I have decided to apply a Parental Advisory to the CD principally because I do not wish to end the innocence of any child by accident. On the whole, though, I suspect there isn’t enough shooting and bloodshed in Shuteye Town to attract an audience of Americans under the age of seventeen.

Q: I have to ask one question a second time—is Shuteye Town a book or a video game?

A: I’ll answer with a question of my own—how about your life? Which does it more closely resemble to you? A book? Or a video game?

Q: How am I supposed to answer that question?

A: Ah. That would be up to you.

Recent Comments