Has there ever been an ‘unperson’ in the modern history of the United States? The answer to that question is a resounding yes. His name was Augustus Zinsser-Zellbach, a self-made man from Brooklyn who rose to dizzying heights of fame and fortune, then plummeted into an obscurity so deep he might as well never have existed. You haven’t heard of him. His name will turn up in no Google searches. Yet he killed no one, never spent a day in jail, and was once accorded one of mass media’s highest honors. How can this be the case in an open uncensored society such as our own?

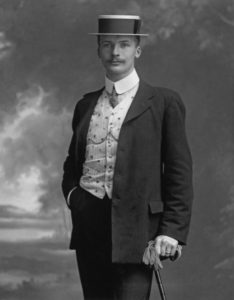

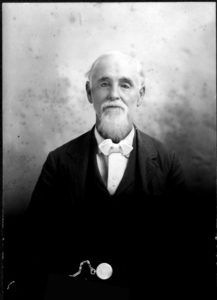

Augustus Zinsser-Zellbach (1898-1950)

ACT I — There Was Once a Boy Who…

The story begins, as we said, in Brooklyn, New York. Augustus J. Zinsser was born to typically mixed American parentage in 1898, on the cusp of the world-changing twentieth century. His father, James, was a generation away from Ireland and worked in the undertaking establishment started and still being run by young Augie’s immigrant namesake, respectfully addressed by almost everyone as “Mr. Zinsser.” Augie’s mother, Flora, was herself an immigrant of German roots by way of Canada, and her devout Lutheran heritage made for an uneasy union with hubby James — or Jay, as he was known at the local watering holes. In addition to Augustus, the couple had a firstborn daughter, May, who inherited her mother’s vocal disapproval of her father.

Despite quarrels about Jay’s drinking over the years, the old man — Mr. Zinsser even inside the family home — managed to maintain relative calm in the household. According to his grandson’s later recollections, he had a knack for grave teasing that insulted no one but drew laughs in tense situations. He could end even loud marital arguments by means of self-deprecating non-sequiturs. “Were you admonishing me, children? For a moment there I thought I’d put my hair on backwards again.” Always ridiculous and straight-faced. Never the same twice. The boy adored him. The two were inseparable outside of school hours, including the hearse runs on funeral days (both of them “dressed to kill” as they joked to each other without smiling). Even May liked the old man well enough. He’d made a present to them of his own boyhood tin soldiers, half to each, which won her heart.

What does any of this have to do with a mighty rise and fall in American fortunes? Those early years with a doting grandfather who kindly ruled the Zinsser roost were the opposite of what was to come, a series of momentous events that forever changed the direction of Augie’s life. In 1907, when the boy was nine, Mr. Zinsser fell down the basement stairs and broke his back. He survived but his life came to be circumscribed by the wheelchair he now needed to move about. In a walkup building (living quarters on third floor, funeral parlor on the second, “lab” facilities in the basement), he could no longer operate the business and was confined to a single smallish living area. This turned the Zinsser world upside down.

Jay had to take over the whole of the business. Before he had been comfortable in the role of, essentially, the maître d’ of the ground floor funeral parlor. All the rest of the work was the unflappable Mr. Zinsser’s job. Embalming, dressing, and preparing the bodies cosmetically, driving the hearse, calling on the bereaved before and after the funeral, and even presiding as a lay eulogist in the services held from time to time at the parlor. He did all the financial side as well, billing, accounts payable, collections, dealing with suppliers, and serving as liaison with priests, ministers, and rabbis. Nobody knew what all his responsibilities entailed. No one asked. Until the accident.

Now it was all on Jay, who responded by drinking more, having more quarrels with Flora, making an enemy of May and a stranger of his own son. Early in 1908, in a show of desperate bluster, he purchased a brand new Locomobile hearse with the last of the rainy day cash Mr. Zinsser had socked away in his sock drawer. Flora was apoplectic. Business was bad and getting worse, she was taking in washing now to help pay mounting past due bills, and she claimed the Locomobile, which doubled as family transportation, was much harder to drive than the ancient Model T that was always good enough before.

She must have been right, one evening when Augie was about 12, shortly after Mr. Zinsser’s Quiet Death, Flora was traveling to an evening meeting of her group across town and accidentally ran into Jay returning home in the dark after a business get-together down the street. Actually ‘ran into’ is less accurate than ‘ran over,’ which left Jay’s legs squashed and bleeding like his father’s before him. He recovered sufficiently to return home some weeks later, but ironically and fatally, suffered a fall of his own down the basement steps as he was transferring from the wheelchair to an amateurish slide contraption he’d built to get down to the lab. Always a tinkerer, he had ‘tinkerered’ himself to death this time, as May waggishly put it. The coroner, a longtime associate of the business, laughed when he heard this. “More likely ‘drinkerered’ himself to death,” he muttered loudly enough to be heard in the neighborhood.

There were some, mostly Irish, who had doubts about two crippling accidents to the Zinsser men and two basement falls, even if circumstances differed between father and son. Flora ignored the talk and did two strong-willed things. She took over the business and resuscitated it with a new kind of client, widows of men who had died while working for companies with deep pockets. These could be found throughout Brooklyn, not justbin the neighborhood. She became a kind of compensation counselor, instructing her new and potential clients about the kinds of accidents that might be paid for by a big-business settlement. Whatever money she made was saved out of everyone else’s knowledge and reach. May may have known more than she ever let on, but Augie’s relationship with both mother and sister continued to decline on a steeper curve than it had been on before.

He did to learn to cook, though, because his mother’s evenings were increasingly taken up with her new passion, leadership in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), an environment and a cause in which she thrived, grew, and acquired real political clout. Following in parallel footsteps, May became similarly active in her late teenage years in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. While the women in his life protested and carried signs with big pointed handles, Augie found old bound and printed cookbooks once collected by the grandmother he’d never known, and taught himself what he could with the modest but not meager household allowance his mother gave him. He discovered baking, and crêpes, and coq au vin (made with grape juice aged in the closet), and best of all pommes frites and Golden loaves of French bread. He frequently ate dinner alone though, except when he got a visit from an old friend of his father’s who had heard about “the boy who could cook like a hotel chef.”

The old friend was also very much interested in the political activities of Flora and May. As their devotion to their causes appeared to reach near simultaneous fruition with the passage of the 19th and 20th Amendments, he confided in Augie, “You got to find a way out of here, son. Their heads is going to explode with all their new female pride and power. Don’t be around it anymore than you have to.”

They discussed it over Augie’s concoctions with patisseries, hors d’ouvres, entrées, and fromages, and within months, the motherless sisterless boy was launched into a daily train commute to and from Manhattan, where work as a busboy was easy to find in the Prohibition world of speakeasies and well connected hotel bars.

This was the biggest turning point yet in the life of Augie, now Augustus, who was leaving Brooklyn in the rearview mirror not just physically but spiritually as well. The break was real, a sort of fracture, but it wasn’t complete. After Jay’s death Flora had abandoned the Zinsser surname and returned to her maiden name of Zellbach, reflecting her German (and Lutheran) forebears. She’d made it legal in court, and required Augie to register for school as Augie Zellbach, a name that appeared on every form of identification he had so far acquired. In New York City, he changed the rules of the game. He kept the Zellbach to avoid confusion, but he added the Zinsser back in, along with his sainted grandfather and martyred father. The hyphen that joined the two surnames was like the connection in his soul between Brooklyn and Manhattan, equal in reality if not in affection. Because the young Augustus Zinsser-Zellbach was head over heels in love with that island of brilliant skyscraper dreams he had seen only as a steel and concrete silhouette before reaching his age of majority. Twenty-One. Also the name of a fabulous club where he was on the waiting list for part-time work. Drum flourish and cymbal crash. The end of the beginning.

From here, we’ll let the pictures tell the tale, just so you can get the raw feel of a story played out in the press and tabloids. Later, there will be an epilogue though, an attempt to make sense of what happened here. Look for it.

Flora and May Zellbach

Literary Prohibition

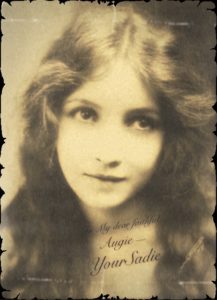

The Love Of His Life

He went to school and fell in love down the street from the Parlor.

The ZZ Taxi Taxi, 1924

The T4 ‘Tracker’

The Christie Co. ‘CC Safe’

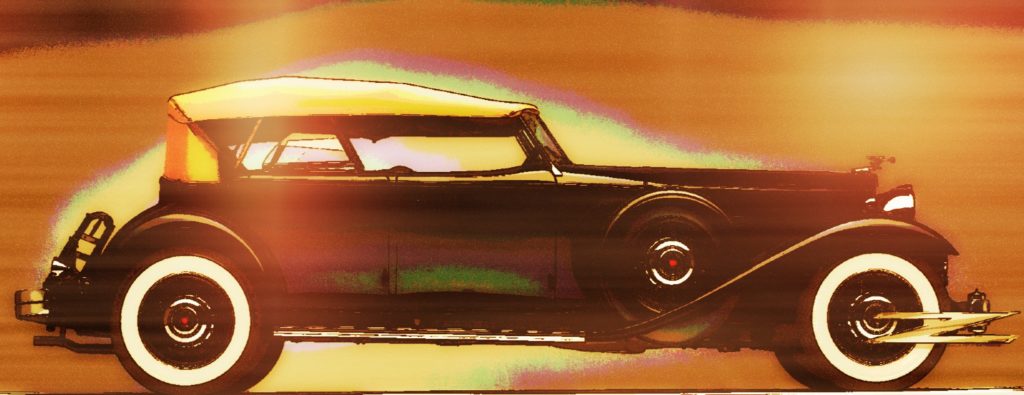

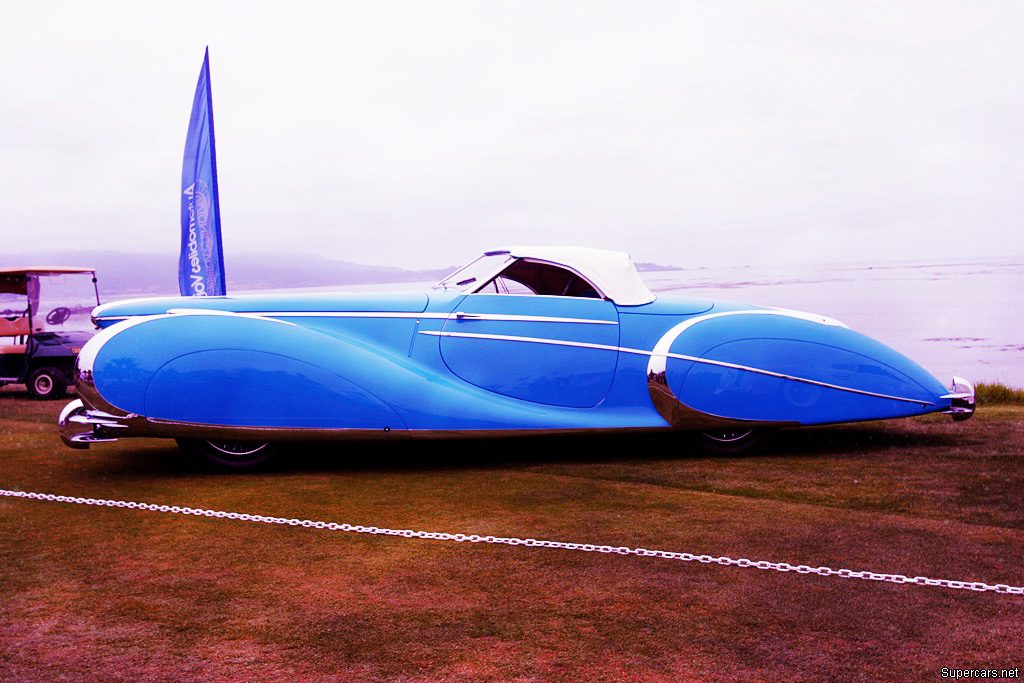

An early artist’s rendering of the 1930 ZZ Model 19R

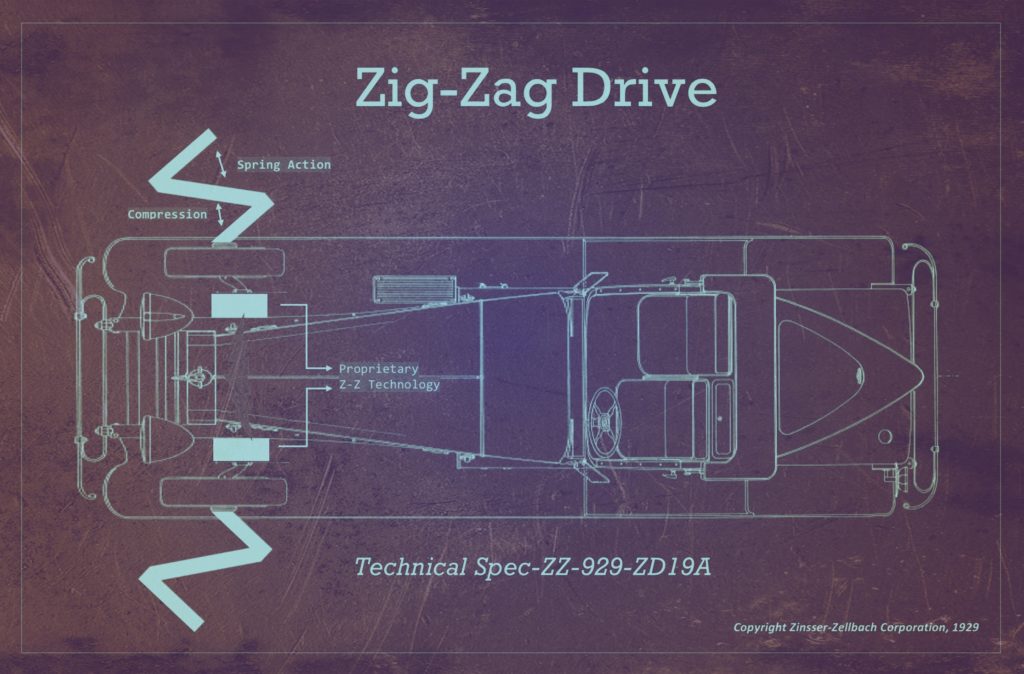

Blueprint schematic for Zig-Zag Drive

The first advertising campaign was not well received.

The monster prototype, the ZZ 24I, code named The Invulnerable.

The 1930 ZZ 18L

The 1930 ZZ 12R

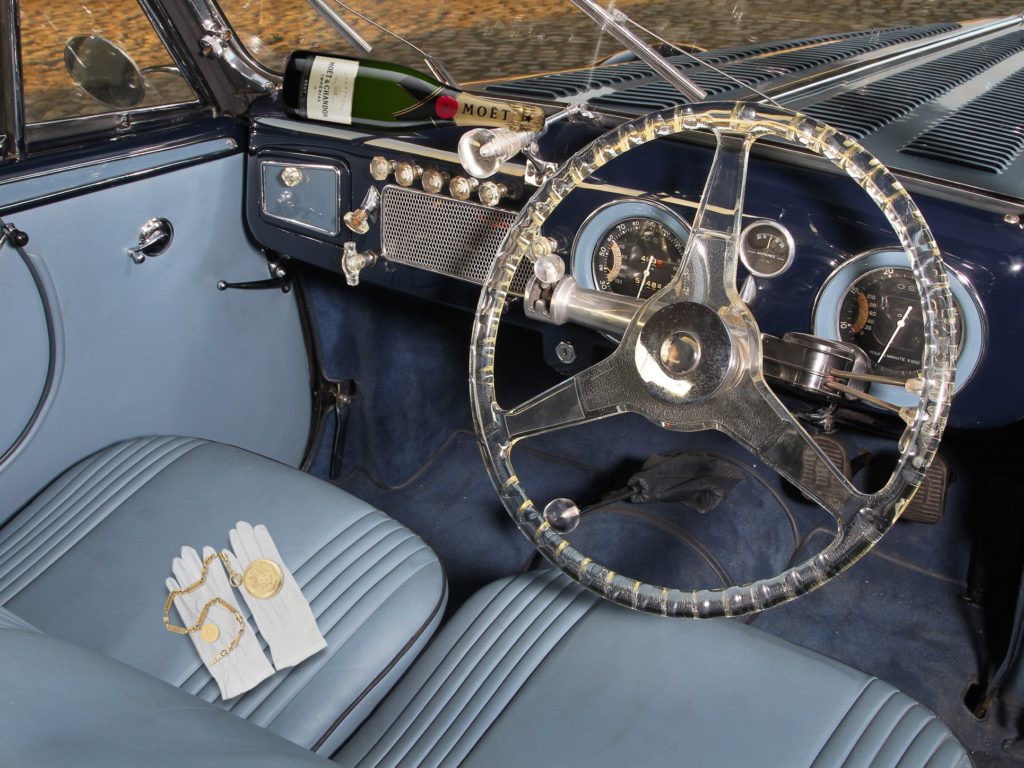

Cockpit of the ZZ 12R

The driver’s seat of the ZZ 12R

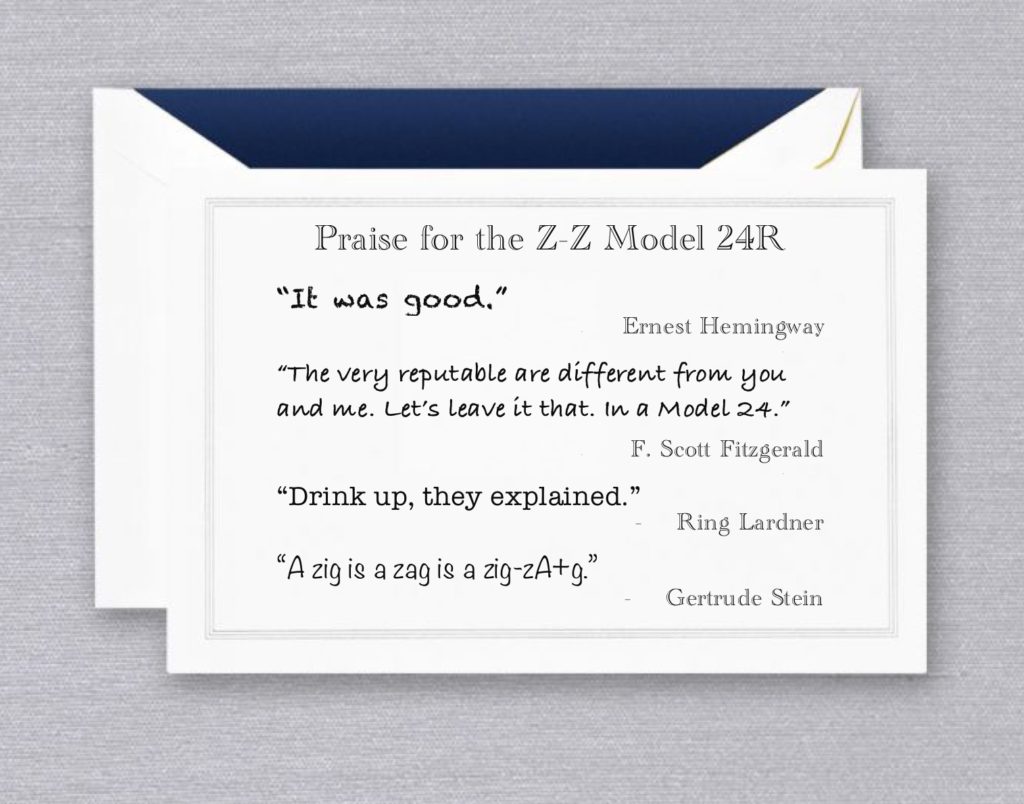

A discreet, high-toned sales campaign succeeded brilliantly.

Newspapers and magazines were full of photos and renderings of the ZZ Model 24’s dramatic (and hideously expensive) Open Book Grille. The car was a Star.

Augustus bought a vast estate in Newport RI with his profits.

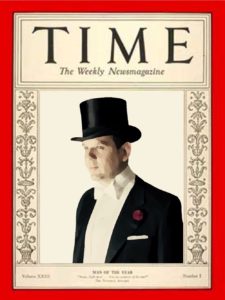

The Pinnacle Of Fame. 1933. Time’s Man of the Year in 1932 and 1934 was Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Heady company for an undertaker’s son.

Zinsser-Zellbach became obsessed. He had to have that Nobel Prize Cup.

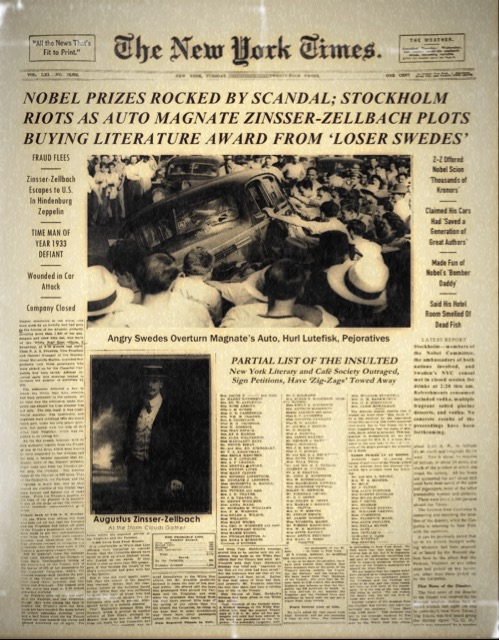

Then the Catastrophe.

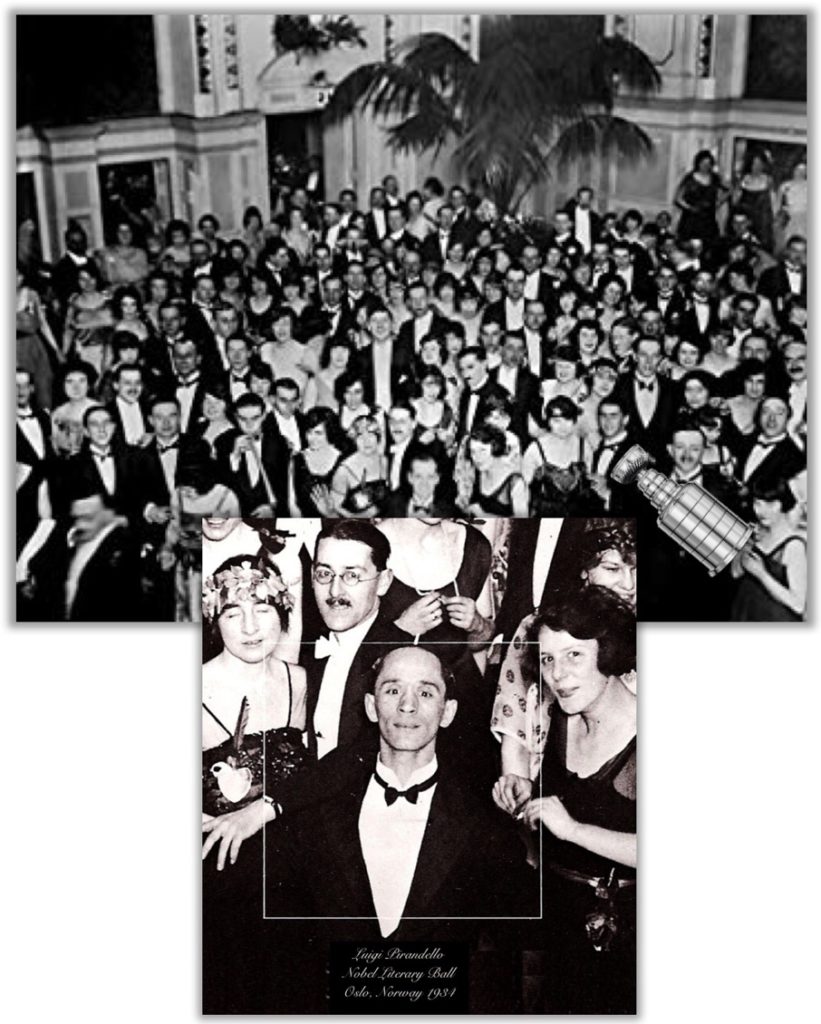

The Nobel Literary Ball and the 1934 Cup Winner Luigi Pirandello

Pirandello partied for days, all over Italy, and everywhere else too.

Back in the United States, every Zinsser-Zellbach vehicle, every part, every building, every scrap of documentation was destroyed.

Zinsser-Zellbach was a broken man.

His car was found abandoned in the seaside town of Menton, France.

The interior was neat as a pin. There was no note.

Zellbach’s tuxedo was neatly folded and left behind with his shoes, top hat and stick. Still no note.

The interment drew shock and ridicule.

The belated monument is still a mystery.

The one last ZZ-24 is not utterly destroyed. It is resting but not in peace.

And that haunting green citronella light.