Most of you have no idea what it’s like returning to the U.S. by sea. I do. Via the Italian Line Leonardo da Vinci. We survived a hurricane to get home.

An edge I have on most all of you. I confronted my own mortality at the age of nine. The ship nearly, very nearly, went down. I spent an afternoon and evening watching grand pianos roll across the ballroom, people vomiting in their frightened sleep, women hugging their children in panic so tight you were afraid they’d suffocate them. And outside the windows of the Promenade deck waves so high and threatening that each one seemed aimed at taking your life. But I was nine and therefore immortal. My fears were for my parents and my sister. Extreme fears. Though I knew I, in the worst case, would bob to the surface like a cork. Boys. You know.

We had been living in Paris for months. I had fallen in love, for the first time, on the French Riviera. Her name was Edith. She was a singer in a restaurant. She kissed me. My family never stopped ribbing me about it.

Our return was premature, unexpected. Our home had been rented out. So we had to rent another one. Which is where one of the great affiliations of my life was born.

His name was Cassius Clay. The sports press didn’t like him. He was brash, boastful, and vain. He’d won an Olympic gold in boxing and was working his way up the professional ladder. He narrowly escaped a career-ending knockout because he had a canny trainer. He broke all the rules. Hands are supposed to be up by the face, not at the hips. But he insisted he was the greatest. I, who had already fallen in love on the Riviera and nearly died in a hurricane at sea, was all in favor of breaking rules.

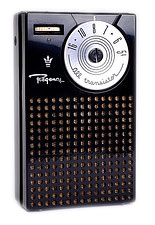

So. On the night Cassius Clay fought Sonny Liston for the heavyweight championship of the world, I was listening on my transistor radio, under the covers, keenly aware that all my other classmates were rooting for Liston because he was favored 7-1.

Under the covers you sweat a lot. But I also read a lot under there. Hot stuff (“I Capture the Castle”) makes you sweat too.

Cassius Clay won. Dazzling speed, a jab like a spear, and a right hand like a club. Hurrah. Then he crossed us all up by declaring himself a black Muslim.

Hell. Where he lost most of all of you. All of you who cannot imagine what it’s like to climb into a ring with a man perfectly able to kill you. The others, the ones who cannot imagine, yell “Coward!” when he says he has nothing against them Viet Cong.

Truth? Never ever been a prizefighter with the speed, accuracy, and footwork of Muhammed Ali. Why he had to be destroyed by mass media.

They took away his title. I saw him in person in the Harvard IAB and he was more than I expected. He was beautiful physically, impeccably suited, and he recited an address he had obviously written himself and memorized, no TelePrompTer involved. He got a standing ovation, nothing patronizing about it.

You could have written his bio then. The fastest, dancingest, greatest heavyweight boxer ever. Then came the return. Older, fatter, slower, Ali set about reclaiming his crown. He lost to Joe Frazier. Knocked down by a 15th round punch and yet back on his feet in a second.

The moment that demarks the second half of Ali’s career. No more dancer. The fighter you can’t knock out. Completely at odds with his early bio.

Seven rounds against Foreman in Zaire. The greatest puncher, probably in history, pounding on your middle for 20 minutes. Coward? I saw this in grad school after a midterm exam. You should have heard us yell when Ali finally came off the ropes and demolished Foreman with about 20 punches in 10 seconds.

But Ali is a self promoting narcissist, right? Why he retired after the Foreman fight. Never gave Frazier a chance for a rubber match. Oops. He didn’t retire. Old, slow, and shuffling, he still gave Frazier a final shot. Seemed like a poor decision through round 13. Ali was beaten. Unless…

The bio we’d write today would say here’s a fighter who took more knockout shots to the head than anyone before him and stayed standing. a miraculous combination of Sugar Ray Robinson and George Chuvalo. Because, you know, no able man ever changes. He just sends more money to Yale. Kewl.