From a manuscript you’ll get to see later, an exegesis on a screenplay I wrote with a great friend in 1980, meaning 35 years ago.

Punk Monks

From 1978 to 1982, I lived mostly in Philadelphia. It was not a particularly prosperous time for me. This was no one’s fault but my own. I had fallen off the curve of conventional career pursuits, in large part because I wanted to preserve my concentration for writing, although I wasn’t making satisfactory progress there, either. My sense of being out of tune with the literary establishment was so extreme that I couldn’t bring myself even to submit the few stories I had finished to the “little magazines”. Instead I alternated between experimentation and self-absorbed narratives of a fantastic nature.

For the better part of a year, I worked with a collaborator on a screenplay called “Norman Rules”, which I had originally conceived as a novel. As I worked on it, the material became more and more insistent about being a movie rather than a book because its most powerful elements were visual. It employed a premise that still intrigues me, although I have never been able to solve some basic problems that emerged in the writing. I mention it here because “Norman Rules” was the vehicle that surfaced my interest in punks, which I had seen during visits to South Street but had taken little conscious note of until they muscled their way into the plotline of my story.

It was a bizarre story to begin with. Raised an Episcopalian, I knew that it was Henry VIII who, in order to consolidate his political power over the infant Church of England, had abolished the monasteries in that country. For satirical purposes, I chose to repeal this historic event, which enables me to create an alternate time present in which the sixties revolution manifested itself as “Reformation II”. The centers of protest and violence were thus not universities but monasteries, and the catalyst for upheaval was not the Vietnam War but a mysterious monastic ritual that was identified in the minds of protester with the term “Norman Rules”.

Reformation II was more visibly successful than the sixties revolution, and the major victim of its success was my stand-in for the Church of England, The Anglo-Orthodox Protestant Church. The action of the movie takes place in an Anglo-Orthodox monastery about fifteen years after Reformation II.

The protagonist is a young novice named John who, having failed to be accepted at a seminary, has been assigned to take orders at the Monastery of Saint Ralph.

It has been a dozen years [now now 25 years] since I last worked on “Norman Rules”, but the monastery that constitutes its setting seems today to have anticipated the phenomenon called Political Correctness by about ten years. At St. Ralph’s, the rotten heart of the overturned establishment, the driving principle is atonement for past oppressions. Still a male-only institution, the monastery has renounced its heritage of male power by adopting feminine titles. Thus, the monks call each other not brother, but sister, and the head monk holds the title of Mother Superior. St. Ralph, like all the saints of the reformed church, is alive and well – a fussy transvestite who moves uneasily in an ecumenical circle of jet set “saints”.

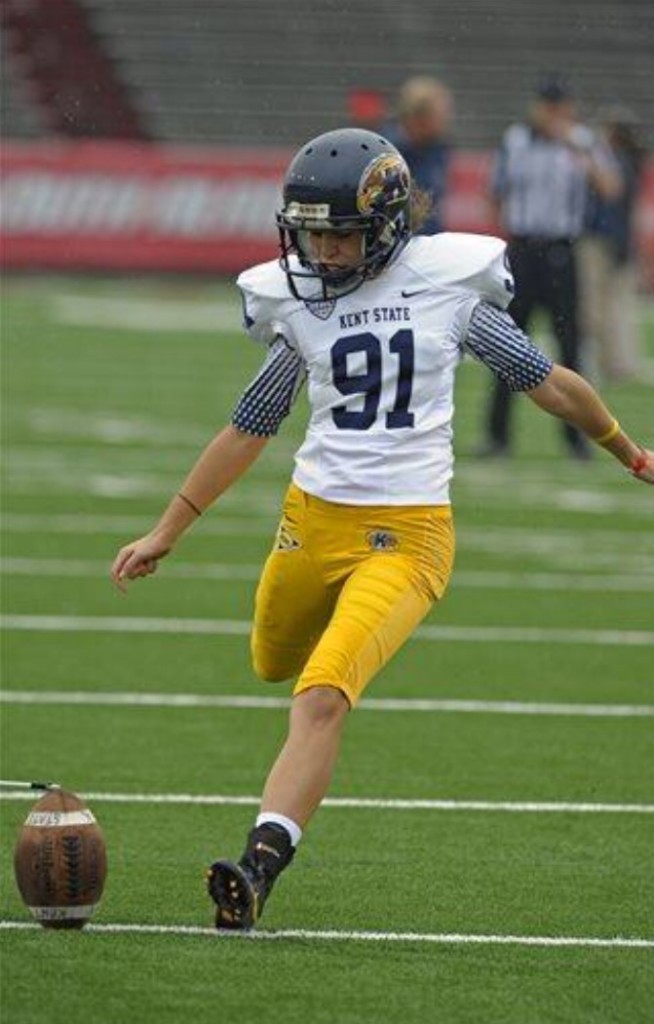

The institution that bears his name is a plastic bubble rising out of the wasteland of an inner city ghetto. For security reasons, the building has no windows, and the only access to its interior is via subway. It is here that “Sister John” arrives and after a humiliating orientation by Mother Clive, is assigned to the St. Ralph’s football team.

Sister John soon learns that in the scheme of things at St. Ralph’s, a football player is about as low as one can get. The monastery is arranged in a hierarchy consisting of three “sections”. The elite of St. Ralphs belong to Enlightenment Section, in which capacity they have light managerial duties and plenty of free time for hobbies like shopping in the monastery mall, writing and painting, and virtually nonstop cocktail parties. The revenue-producing contingent at St. Ralph’s is the Service Section, which (for a healthy commission) dispenses federal monies to the poor and needy of the city, who enter and depart the vast Service Section offices in cattle-car-like subway trains. The bottom rung of the monastery is Atonement Section, which is the repository for all monks deemed unorthodox in their views, including a stubborn remnant of pre-Reformation monks who are known as The Ten. Having taken a vow of silence in resistance to the new order, The Ten continue to be a disturbing presence even though they meekly perform their assigned duties, which are principally janitorial. In fact, the value of Atonement Section lies in its ability to provide a resource for the work that no one else wants to do, including kitchen duty, cleaning, laundry, and maintenance. Football is the worst duty of all, because the permanent state of penance in which the Anglo-Orthodox Church resides requires that its football teams lose every game played against other denominations. Indeed, the rules of the game are continuously revised to ensure that defeat is achieved, even when St. Ralph’s plays against convents of nuns.

What Sister John does not know is that he has been brought to St. Ralph’s to change this state of affairs. The agent of change is Mother Clive’s assistant, Sister Gregory, an enigmatic monk who once played a leading role in the Reformation but then fell out of favor and disappeared. Upon his return, he speedily acquired power through his willingness and capacity to take on the more onerous duties of Mother Clive. One of Sister Gregory’s first initiatives is to recruit new football players, ostensibly to boost gate receipts and thus alleviate the mounting deficit of the monastery, but in reality because he seeks to use football as a means of forever destroying St. Ralph’s and the Anglo-Orthodox Church.

This was the premise I started with. The intention was satirical comedy – highlighted by the abundant visual irony of the monastery and its activities. Inside this opaque bubble, the building was a ludicrous parody of monasteries, featuring linoleum stonework, backlit plastic stained glass, Styrofoam pillars and buttresses, cartoonish chapel frescoes, and a monstrous mall offering Adidas sandals, designer cassocks (for Enlightenment Section only), and as many junk food and gin joints as a modern monk could want.

The plot was to center on Sister John, the gifted football player who builds a winning team and feverish romance with Saint Jenny the rock star. Due to the maneuverings of Sister Gregory, the team finally has to play its championship game under “Norman Rules”, which no one knows anything about but The Ten. And Norman Rules, it turns out, are a barbaric throwback to medieval combat, offering up the prospect of football to the death for the ultimate prize – The Holy Grail.

In the course of drafting the screenplay, however, two things happened. First, Sister Gregory refused to remain in his assigned place, somewhat behind the scenes, as a sinister but mysterious catalyst for the hero’s coming of age. Instead, he roared out of the wings as a character of formidable stature and complexity, barred from greatness only by his inability to find a repository for his frustrated faith. He dwarfed the character of Sister John and transformed the Comedy of St. Ralph’s into the Tragedy of Sister Gregory. This put far more pressure on the climactic game than the original premise seemed able to bear. The last act of a comedy could benefit from a game of football played in medieval armor, but the catastrophe of a tragedy would be spayed by it. I never did figure out how to solve this problem. [Well, I did but had moved on by then, blast it.]

The second unexpected development was that St. Ralph’s, conceived as a holding tank for post-sixties Baby Boomers, began to fill up with “punk monks”. They loitered in the great mall, they shot-up heroin on the platform of the “Monastery Station” subway stop, and they committed acts of vandalism and personal violence within the corridors and shops of St. Ralph’s. And then Sister Gregory began drafting them for the football team, a doomed gang of savages who were destined to become animal sacrifices in the concluding holocaust of Norman Rules.

The punks seemed to be dragging the real world and its consequences inside the plastic walls of St. Ralph’s. They were the next step, the next rung down in the descent of man being enacted within the monastery. Essentially without lines of dialogue, they had changed the whole flavor of the work, and then, in the final game, it was they who rallied most strongly to the aid of Sister John and The Ten, giving up their lives to win The Holy Grail.

I liked Gregory far too much to reduce his stature and force-fit him into a comedy. And I was curious about the punk monks. I liked them too. They were the ones who seemed most at home in my absurd climax, safety pins, razor blades, tattoos, and mohawks went with armor and battle axes just fine. Who more likely to fight bravely to the death than those who already had nothing left to lose? They’d lost everything before they even knew there was anything worth winning. But that’s where their hardness came from, their very ignorance of the hopelessness of the situation. They knew so little that they had no prudence, no respect, no fear – only rage and a willingness to go.

Part of a much larger manuscript called “Inside the Boomer Bible”. Available soon.

Recent Comments