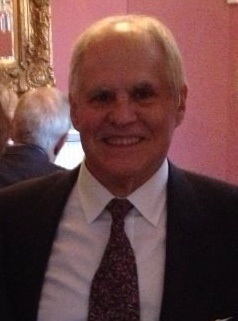

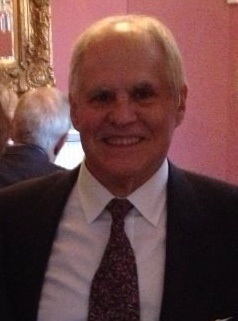

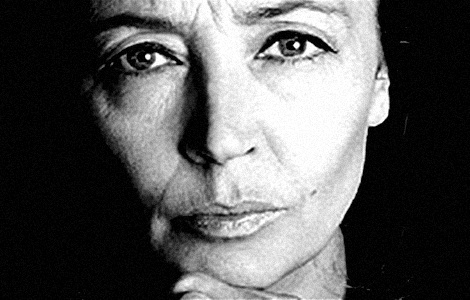

Frank Bogage.

Interesting article at Hotair today. Called “The Smartest Person Who Ever Lived.” The nomination was Isaac Newton, and I can’t disagree. Scientist, theologian, mathematician, alchemist, technologist. Whatever the subject, if he didn’t have the tools, he invented them, including calculus and the scientific method.

I would not, could not dispute this nomination. All I can do is mention the smartest person I’ve ever known personally. As you may have guessed, his name is Frank Bogage. I’ll remind you of the Newton nominator’s criteria:

We must first discuss what we even mean by smart. Colloquially, we routinely interchange the words smart and intelligent, but they are not necessarily the same thing. There is an ongoing debate among psychologists, neuroscientists, and artificial intelligence experts on what intelligence actually is, but for our purposes here, a simple dictionary definition will suffice: “capacity for learning, reasoning, understanding, and similar forms of mental activity; aptitude in grasping truths, relationships, facts, meanings, etc.”

Implicit in this definition of intelligence is general knowledge. An intelligent person capable of understanding quantum mechanics is useless to society if he is completely ignorant. So, a truly smart person will know a lot of things, preferably about many different topics. He should be a polymath, in other words.

Finally, there is the element of creativity. Creative people think in ways in which most other people do not. Where society sees a dead end, a creative person sees an opportunity.

What Frank was and is. In college he studied urban development and did onsite archaeology on the Anasazi peoples. He divined how human organizations worked. Then, inexplicably, he became a computer jock. He built microprocessors by hand, he learned machine code, he sussed out systems architecture and systems analysis on the wing.

I learned about him before I ever met him. I went to work at a company called Datapro, where they hired people who could write and might learn something about computers. And they hired people who knew about computers and might be taught how to write. I was an English Major lost at sea. Our business was documenting and reviewing computer hardware, software, and peripherals, including communications. Our most senior editor had worked on the original Eeniac project. We were supposed to be the gray matter of the biz, much in demand by everyone who wasn’t IBM. My editor kept talking to me about Frank Bogage, the smartest guy who had ever worked at Datapro. I took seminars, listened in the hallways, heard much more about the legend of Bogage. I got sick of hearing about him.

By accident, I suppose, I went to work at the same company that had hired Frank. He showed up at my cubicle on the morning of my first day. I forget what questions he asked me. After that we somehow became inseparable. He had made a judgment on incredibly slight data. He chose me as a partner in corporate crime. Jersey boy buccaneers. He would teach me what I didn’t know. He’d decided I could learn it.

Which was the third leg of his four-footed stool of polymathematics. He knew everything about everybody. From the temp secretaries to the most ambitious Vice Presidents. It’s not that he was a gossip. He was curious, his questions prompted answers somehow, and people told him things they wouldn’t have told their parents or spouses. He had a kind of brusque empathy that made people want to talk.

The executives hated him. Not because he knew their personal secrets, which he did and they didn’t suspect, but because he knew their business way WAY better than they did. He was a walking threat to their authority. They used and abused him nearly to death. They sent him on the road to peddle a flawed corporate networking strategy. He was so creative that he succeeded more often than anyone should have thought possible. Hell on the road. Once he couldn’t remember where he was. Only the sight of a dangling replica of the Spirit of St. Louis reminded him he was in the St. Louis Airport. So he had coffee and proceeded to his next Executive Briefing.

Which he accepted because of the fourth leg of the stool. He was, more than a computer genius or a potential office politico, a family man. He did everything he did so that he could take care of his wife and kids. Corporate advancement wasn’t on his list.

But integrity to his profession and job was. He wasn’t prepared to claw his way up the ladder. But he was prepared to fight to the death for principle. Which we did together. He taught me everything I’ve ever known about the computer industry. His rules — like Gibbs’s from NCIS — still hold true. Microsoft operating systems are all fatally flawed. Companies have never figured out that emails are corporate documentation or how to secure them. Great code is worthless without a usable interface or documentation of how everything works. What sank the division where we worked.

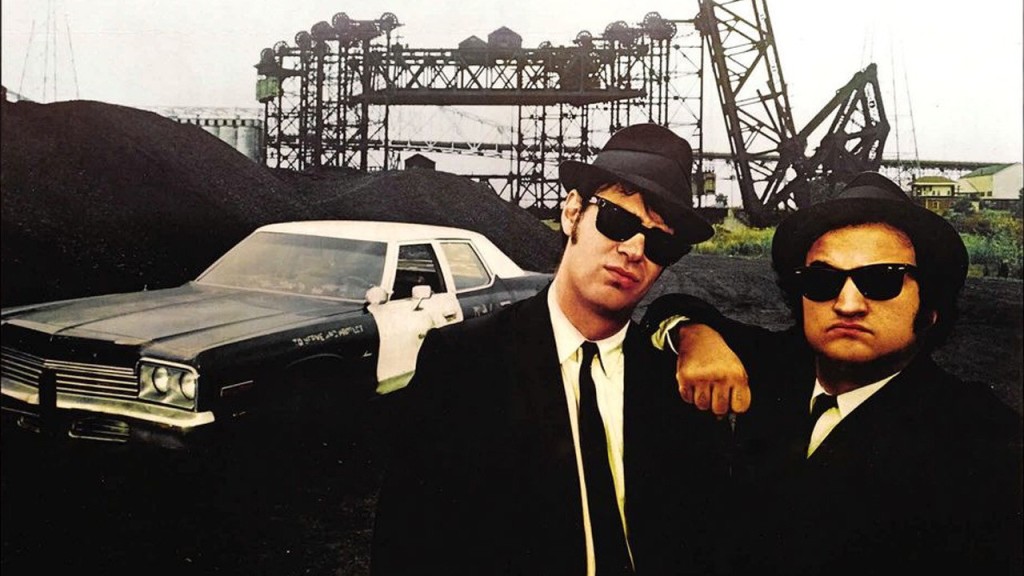

They came to hate the sight of us together. They called us the Blues Brothers.

I provided the car. Because though we were both from Jersey, I was the only one of us who was a motorhead.

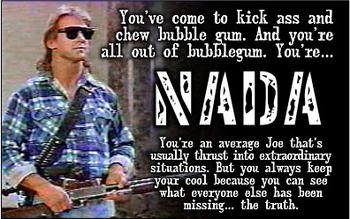

I played my part. But I wasn’t the one — in the midst of a 36 hour day to defeat a disastrous software release — who descended in a glass hotel elevator looking like a suit-and-tie version of this guy.

Call it the central pillar of a four legged stool. The eyes. Black but not evil. Just hard to meet if you had something to hide. Eyes that made executives hate and fear him. Eyes that made other people tell him secrets. Eyes that saw the future of a technology that just got started. Eyes that saw family as more important than all the other fires burning within.

Now he’s a mild mannered grandfather. I saw him at war. In about 16 months I learned enough from him — about technology, people, organizations, office politics, thinking on my feet, courage in the face of bureaucracy — to build a whole career. Until I discovered the fourth leg of the stool something more than a decade on. He’s a great man. And the smartest I’ve ever known.

God bless you, Frank.

Recent Comments