Interesting bit of querulousness at The Corner today, courtesy of NR enfant terrible Tim Cavanaugh:

The astute media critic Jay Rosen — who as far as I know is neither a conservative nor a Republican — goes full J. Jonah Jameson on reporters’ lazy assertions that the GOP congressional majority needs to “show it can govern.” Rosen sets up several phrasings of this truism– from the U.K. Telegraph, The New York Times, and NPR Congressional reporter Ailsa Chang — before knocking them down:

These are false statements. I don’t know how they got past the editors. You can’t simply assert, like it’s some sort of natural fact, that Republicans “must show they can govern” when an alternative course is available. Not only is it not a secret — this other direction — but it’s being strongly urged upon the party by people who are a key part of its coalition.

Now keep in mind that for NPR correspondents like Chang, a ‘factual basis’ is everything,” Rosen writes. “They aren’t supposed to be sharing their views. They don’t do here’s-my-take analysis. NPR has ‘analysts’ for that. It has commentators who are free to say on air: ‘I think the Republicans have to show they can govern.’ Chang, a Congressional correspondent, was trying to put over as a natural fact an extremely debatable proposition that divides the Republican party. She spoke falsely, and no one at NPR (which reviews these scripts carefully) stopped her.”

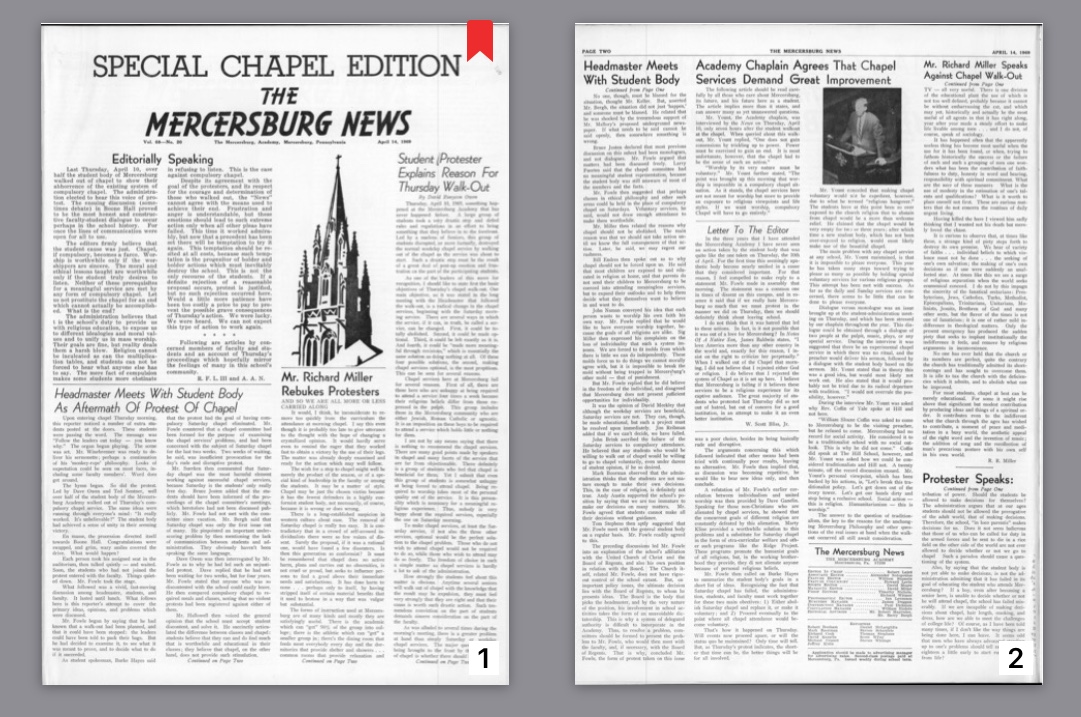

Which got me to reminiscing. Almost immediately after I became editor of the Mercersburg News, I experienced an almost allegorical journalistic challenge. It was 1969, the year of all years in the iconic sixties. A school which had always been its own self-contained world was suddenly bursting with the desire to be relevant in the exotic new youth culture. In a mere two years, drugs — chiefly marijuana and LSD — had rolled into a campus where drinking a beer used to be an expulsion offense. Seniors contemplating next year’s radical campuses were looking for an opportunity to prove their Woodstock manhood.

Easy answer? Break an ancient ironclad rule in a dramatic way. Led by four year boys, the would be radicals staged a mass walkout protesting our required 8:45 am Saturday chapel service. Dramatic it was. Staged on a Thursday for maximum surprise, the service was up-ended at once. Half the school exited after the opening prayer. I stayed. My best friend left with the cool guys. Our aged headmaster, who used to reward his best students with musket balls he’d dug out of the turf of Gettysburg, was stunned. He took the pulpit to call for a school meeting in the auditorium RIGHT NOW.

Those of us still in chapel passed the word and the walkout kids were happy to obey this particular order, which promised an opportunity for “airing all views.”

I took my seat near the aisle in the auditorium, and then I saw I was being signaled by the faculty adviser of the News. He was a former John Lindsay speechwriter, one of the radicals of that day, a five pack a day smoker, and he bent toward me to ask, “Are you taking notes?” He was smiling a mile wide smile.

Hadn’t occurred to me. But boy did I take notes. The headmaster recognized every student with a hand up. Everything spilled out, every resentment, every chafe against rules, every ounce of rebellion against our disciplined life, and he stood there like the man he was and took it, clearly grieving that his school had been sucked into the cultural hurricane of the age.

When the meeting — or manifesto, or tantrum, or political protest, or whatever it was — ended, I hunted down my chain-smoking mentor and asked him a single question: “Can I put out an Extra of the Mercersburg News?”

Within an hour I had permission. Sixty-eight years of the Mercersburg News, most of the last 40 or so of which, the paper had been the best newspaper in the private school world, but never ever had there been an Extra, maybe not in the whole private school world. When is there ever actual news, actual trauma in a closed community?

Which is when the journalism questions began.

I personally opposed the walkout. With every fiber of my being. But I was the editor of the Mercersburg News. How did one get chosen for the position? Lecture articles. Every Monday, some outside professor, writer, or scientist came in to educate the whole school during the last afternoon class period in the auditorium. One poor slug like me was assigned to take notes and write up the whole lecture, 25 to 27 column inches, for delivery to the newsroom before class on Tuesday morning. The paper had to go to bed by late Tuesday, so it could be published by Saturday morning in student mailboxes.

The guy that did the most lecture articles became editor. Why? He had to learn that his job was to report, not characterize, not comment. The speaker said this. He said that. There was no hint of review permitted. It was a lesson in the ABCs of journalism. Why Mercersburg had won so many awards. Our ancient Aussie carillonneur adviser prior to my Lindsay activist had established the tradition and the discipline.

When you became editor, you could express opinions in editorials. No one else on staff could.

So I went to the smartest faculty members and students I knew on both sides of the walkout controversy and asked for equal column inches from both. They all agreed to participate because they believed I would be fair. I also wrote up — maybe 30-40 column inches — of reportage from my notes of the school meeting, without a single snide comment or intimated dismissal. Just what happened, what people said. What I had been taught.

Even my editorial was even-handed. I realized after reading the contributors who had volunteered that there really were two sides to the walkout. I still thought it was a bad idea, but it was also true that there was no longer a closed community. We were all being drafted into the culture war of the sixties. And much as I might defend the Vietnam War, I still loved my Stones. I was torn just as the school was torn.

The Extra was published on the Monday following, in less than half the usual production time. (On the News staff side, it had been a solo effort at that.) A milestone for the school and for me. I was more a journalist at fifteen than the NPR glunks Jay Rosen is talking about. Why?

Multiple reasons:

1. I was heir to a tradition of excellence perpetuated for many many years by an exquisitely literate and conscientious adviser named Bryan Barker.

2. His successor was a liberal in the old sense of the term. He kept talking about the New York Times. (In my subconscious, he looks like FDR, with a cigarette holder. Actually it was just a cigarette.) He personally approved the dead equal balance I sought between pro and con on the walkout event. He was delighted with the newspaper product, not seeking propaganda.

3. I had been taught how to write journalistic copy, omitting the emotional and prejudicial words even to a fault.

4. The physical process of producing a printed newspaper enforces a respect and discipline of its own that requires one to live up to it.

I imagine most can work their way through to understanding the first three reasons. Why I choose to dwell on the fourth.

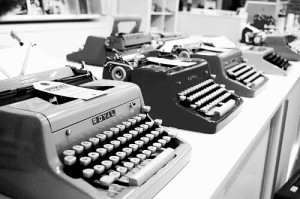

The Mercersburg News was a very physical creation. It commanded respect on that account alone. The newsroom looked a lot like the photo up top, though the typewriters weren’t so spiffy. But they were manned by unpaid writers who produced eight pages a week, ranging from sports coverage by people who were trying to be Red Smith to columnists who were trying to be Woody Allen or James Thurber.

There was also a row of wooden drawers containing woodcuts, only partially represented by this image of press trays. Commonalities: wood, shallow slots, sense of age.

All right. Let me walk you through it. Images in those days were blocks of wood with something on top, a quasi-daguerreotype of a camera photo or a metal relief sculpture of some kind.

Either or both had to fit into a physical page created by a Linotype machine.

Here’s how it works, you see. The Extra was the first time I had to oversee it all. Get the copy, pick the woodcut of the Chapel (which would be our only graphic in four pages), and hustle everything to downtown Mercersburg.

Then comes the Linotype machine. You have no idea. You’re staring at the world’s biggest typewriter.

The columns of writing weigh many pounds.

Yeah. Wanna hear? Go for it. Humbling.

I stood over his shoulder to watch the Extra being born. I felt like I was being whipped. What it sounded and felt like.

Think I’m boasting, talking triumph? No. Five years after the walkout, ten of the kids I’d known were dead. Mostly NOT Vietnam. Drugs, suicide, and other misadventures. I knew I’d witnessed a sundering. One that continues today. My Extra was ineffective puffery. But I was trying. Which when I look at it from my age doesn’t count. Like so much of journalism. But at least it was that. An attempt to see all sides.

I’ve reached an age of self examination. Thinking most of today’s “journalists” will never get there. So be it.

Mercersburg me.

-

Thank you for sharing this.

Comments are now closed.

1 comment