I’ve been having a conversation with my dead dad, staring at the ceiling and asking his forgiveness. I let him down. My life in many ways has been the opposite of his. He always told me, “I want you to do whatever will make you happy. I don’t care if you want to be a garbage man if it makes you happy.” But he didn’t really mean that. He wanted me to be more like him, dutiful, traditional, and polished. He felt pressured by his dad to be an engineer, which he never wanted to be. He thought my better choice would be to become a lawyer, which I believed because he told me I would be so good at it. This gets us through adolescence, after I’d been through his prep school, where I never realized I had any choice not to go to, just as my sister was entering Vassar, where his sister had gone and my sister automatically matriculated after gaining early admission. Between the two of us, at the height of the most competitive period of college admissions ever, the two of us applied to exactly three colleges. (At the time a little less than $50 in total application fees.)

This is not a bragging jag. It’s the backstory for what happened in my life. The family plan was that I would go to Princeton and then to some great law school that wasn’t named Harvard. Because the only academic stricture ever placed on me was that I couldn’t go to Harvard. My father’s first postulate was that Harvard was the worst of the worst, although every other Ivy school was reverenced.

Why it was so awkward that the only two colleges I applied to were Yale… and Harvard. About the same time my sister got her early admission to Vassar, I got a letter from Yale, offering something called a Yale National Scholarship, meaning if I ever ran out of daddy’s money, they’d pay the rest of my way through. You know. Kind of an honorary thing.

My parents were very proud. My prep school guidance counselor was proud. He was a Yalie. But in those days, the moment of truth was April 15th. On that day I received a letter from Harvard offering me an “Honorary Freshman Scholarship” and the distinct possibility of “sophomore standing,” meaning I could graduate in three years instead of four.

The most difficult conversation I had ever had with my dad. “I got into Harvard. I want to go,” I told him on the pay phone in the dining hall. Long silence. “Okay,” he said. “If that’s what you want, do it.” He felt better when he understood the financials of the sophomore standing option. I was sixteen. He figured I would grow out of my folly.

Cut to freshman orientation at Harvard. It wasn’t a few days of feel good stuff the way it is now. It was a meeting of the entering class at Harvard’s ugliest building, Memorial Hall. Just two days before classes.

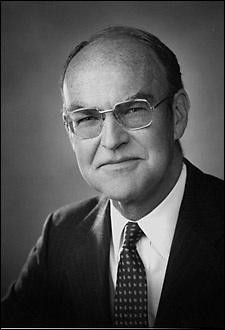

It was the Dean of Admissions who addressed us. Chase Peterson. No one in the gallery who didn’t know who he was. We had all written our application essays to him. He was the Colossus who stood astride the portal of Harvard. It’s all too big to comprehend. When you get accepted you don’t just receive a letter. You get a piece of parchment with your name rendered in beautiful calligraphy announcing that you have been chosen. In those days, the percentage of those admitted to Harvard who went to Harvard was 85 percent. The second best in this metric was Yale at 60 percent. Harvard was dying and going to heaven. Nowhere else could compare.

Chase. His job was to congratulate us, assure us of our superiority, and guarantee our success in the adventure of life. Here’s my best recollection of what he said: “I suppose I should tell you you are the best and the smartest and most promising of all the youth in the land. But I have to tell you the truth instead. We are all gathered here, in a crumbling throwback to the 19th century, to let you know that you are the result of a fairly arbitrary selection process and none of you should feel that anything is assured.”

There was a murmur in the great hall. Unless it was a kind of gasp. Hard to tell about the acoustics of crumbling throwback buildings.

Cut to a day or two later. By college mail I received a summons to the office of the Dean of Admissions. Oh shit. The Colossus has discovered I’m not worthy. Oh shit.

I made my way to the administration building, a somewhat garish and frighteningly modern edifice opposite Harvard Yard. Sitting in the modern waiting room, you feel that none of Harvard’s gentlemanly traditions will protect you. You’re another unit, another widget easily expelled from the machine.

And then someone else ambled into the waiting room. My prep school roommate. My best friend. The guy who had talked me out of applying to Princeton in the first place and into applying to Harvard because Harvard was so hard to get into and it was, in his mind, where I belonged. His dad had gone there, but Russian Jews don’t have quite the in on college admissions they once did. My friend Howard Levin had applied to Harvard only to honor his dad, desperately wanted to go to Columbia, and added schools like U. Rochester, U. Cincinnati and similar as his mid-range, and then ticked off Boston University as his fallback.

By the time we graduated, Howard had been rejected by every school he applied to except Boston University and one other, which had both wait listed him. The other one was Harvard. He tore up his diploma. Then he spit on it. Four years of work and pain and he wasn’t in college. He had a genius for self pity I’ve never seen equalled.

But late in August, I got a call from Howard. As usual, he started in the middle. “I was getting ready to harikiri myself and go to f***ing BU when the phone rings and it’s Chase.”

“Chase?”

“Chase Peterson. I was the next guy on the waiting list and some Lawrenceville shithead decided he wanted to take a few years off to find himself.”

I was appropriately dignified about his new opportunity. “Holy fucking Christ. HOWARD! What are the odds? We’re both going to Harvard. Four years of hell. And we’re the winners.” He was typically enthusiastic. “It was an accident.” It had been two decades at least since our school had sent two graduates to Harvard. An accident? No way.

And now here we were in the outer office of the guy he had aimed me at and who had somehow reached out to save him. Weird. Which was the title of the personal essay in Howard’s Harvard application.

We didn’t wait long. We weren’t being punished. He was a handsome friendly man. His eyes kept moving back and forth between us. Calm, curious, appraising.

“I didn’t mean to alarm you,” he said. “But I just had to see.”

We reacted in our distinct ways. Howard plucked at his long black hair, obsessively, and I leaned back in Celtic fight or flight mode, ready to say something unforgivable.

“You were roommates,” Dr. Peterson chuckled. We admitted it. He ignored us. “I just had to see the roommates who were the very first and the very last admitted to your class at Harvard.”

Howard and I looked at each other. From both ends, we had exactly the same thought. This is winning a lottery of lotteries of lotteries. And we’re the ones who did it. Fuck the assholes of Exeter, St. Paul’s, Groton and Choate. We got each other into Harvard from nowhere because we decided to. Between us, there was no more than an eyeflash. We both smiled, manfully, giving nothing away.

Chase wasn’t trying to pin us down. He was just genuinely curious. He wanted to see the chemistry between us. And I think he saw a good part of it. Howard and I were always in the business of protecting each other. I think Chase saw that. Something neither of our families ever did. My folks thought Howard was a bad influence. His folks thought I was a ‘Goodbye Columbus’ subplot. Goy.

Howard died at the age of 40. I’ve been missing his friendship all these years. He died long before my dad did. I suppose these days I have to specify that there was nothing gay about it. We were everything male friendship is supposed to be. We talked and talked and talked from our opposite perspectives, Episcopalian WASP and Russian Jew, and we both could read books by the dozen. I saved him from getting expelled and he saved me from Princeton. He promoted Dostoevsky and I promoted Hemingway and Fitzgerald. And we both lashed out in satire that got us in trouble in the school newspaper I edited. We collaborated on some pieces that I defended him for. When we won those fights I turned him loose and he was scathing.

I could see Chase looking from Howard to me and back again. Who wrote the brilliant essay that got Howard against all odds into Harvard? And I could also see that he couldn’t tell. Because friendship is proof against tells.

Okay. I won’t play footsie with you. I wrote the essay. But I’m a writer. Nothing without material. Howard was an original, too big to be able to write about himself. He found me, a dutiful conformist, and more or less launched me on the mission that has both illuminated and poisoned my life.

There was a chapel walkout in our junior year. The moment when the sixties hit our school. The reason I did the first ever EXTRA in the history of my school newspaper. When I became for the first time a commentator. I did not walk out when half the school did. Howard did. He enjoyed doing it. He’s dead now. But there’s still a part of him in me.

I walk out and I stay. I stay and I walk out. Why my dad and I don’t get along in my dreams. But also why I don’t give up no matter how bad it gets.

Thinking he might forgive me eventually. Though I doubt the Levins ever will. You know how those Jews are. Not Sally, not Rachel, not Janet, not Robert, not any of them.

Because they’re only the best friends you can ever have. If one of them is named Howard.

Call me crazy or delusional or sentimental, but I think Chase saw what he expected to see, wanted to see. Abiding friendship.

And, dad, except for your eternal disapproval, I am happy. Better, I know I used my time here to leave something behind that’s better than I am. So I am content. Which is far more important than happy.

Here’s the sad thing. He’s too dead to hear me. I’m the warrior he raised me to be. Just not in the arena he expected. I think he was English. But I’m a Scot. Makes a difference.

btw, ask Chase if he remembers. He’s still alive, me hearties.

P.S. Not all happy endings. Howard opened a dozen furniture stores. I opened a multinational management consulting practice. His mother decided she could write fiction. Life is beautiful. But what of Rachel? What of Janet? Howard died. More than 20 years ago. None of them has ever reached out to me. Everybody knows Celts don’t feel. Which is our edge. We. Just. Don’t. Care.

SALLY: I miss your son Howard every day. I’m also a better writer than you. If you’re still alive, talk to me.

-

Great story. Thank you, as always, for sharing. If you don’t mind my asking, how did Howard die?

I lost my best friend, too. He’s still alive, but chosen a kind of living death by joining the cult of radical, progressive atheism. He’s not at all the person he used to be and we have nothing to talk about any longer.

Comments are now closed.

10 comments