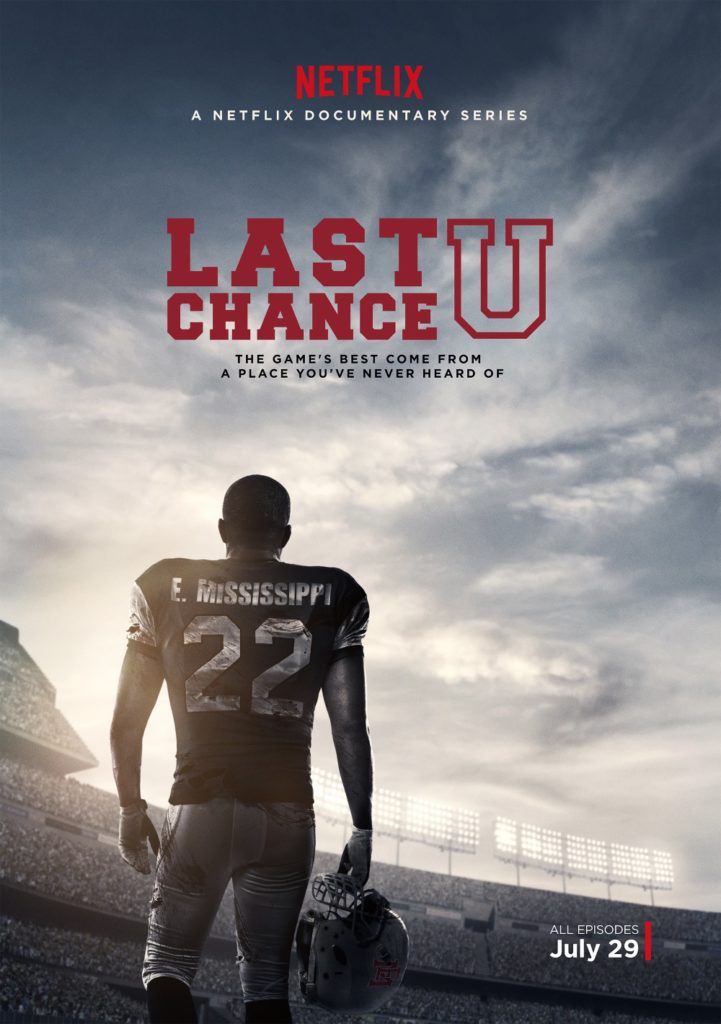

Should be titled “No Chance U.”

The hardest part with this six part Netflix series is to know where to start. It’s so many things all at once. Don’t even know what’s intended by the producers.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=A1eNrHoLTfM

You got preconceptions about the mushmouthed backwardness of Mississippi? Step right up. All of them fulfilled right here.

You got problems with football as a main part of underclass culture? Here you go.

You think government largesse can make hope where there otherwise would be none, take your business elsewhere. This is an awful confrontation with reality.

There’s a junior college called East Mississippi State. You know, the state that nobody who lives there knows how to spell. They’re the best junior college football team in the nation. State of the art locker rooms, and buses, and six different uniforms, and they’re the last chance for football players who can’t qualify for Division I scholarships. A spotless stadium with a capacity of 5000 seats. A record of 25 wins with no defeats and two national championships.

Sound like the American Dream? The American Nightmare is more like it. You watch it hoping that it’s a hope for kids who want good lives for themselves. The reality is that there’s no hope for anyone involved.

It’s a documentary series, which means you hear a lot from the coach, who weighs 400 pounds, has a sweet family and the foulest mouth on the football field you’ve ever heard tell of. There’s also the young woman charged with shepherding the players through the academic path that’s necessary if any of the players will ever get a Division I scholarship. She sounds like Dana Perino. She is earnest. And she fails at every turn. The subplot of two episodes is her attempt to wring an essay out of her charges about the short story “The Most Dangerous Game.” Her students don’t show up for class, don’t meet any deadlines for their essay, and never show the least sign of understanding that their futures depend as much on academics as football, and they don’t care.

Hard to tell if most of them know how to read. That’s how pitiful it is.

The only point. They don’t know how to read. There’s no point in them playing football. They’re just paid gladiators who won’t ever make the grade.

Same with the Division 1 schools. “Students” who can’t study. Not anywhere in Division 1. Except maybe somewhere by exception somehow.

Do away with this crap. Stop pretending that illiterate street kids can pretend to play football. Give them their own minors, like baseball. Class B, A, AA, AAA, do it. They’re 60 IQ illiterates. Let them be gladiators in the NFL. And under. Don’t pretend they ever got an education. They never did. None of them.

It’s like the NBA. 500 jobs up for grabs. A million kids in the streets who have no knowledge of odds think they have a shot. They don’t. Same with football.

Saddest commentary on race in America anybody could have invented if they were the evilest nastiest person in the world. What Democrats call hope.

arge wp-image-15627″ /> What did Grace Kelly say? “She was yar.”

arge wp-image-15627″ /> What did Grace Kelly say? “She was yar.”

Recent Comments